The Centipede Game presents a fascinating paradox in game theory. It’s a seemingly simple game of cooperation versus self-interest, where two players alternately choose to either take a progressively larger share of a growing pot of money or pass it to the other player. This seemingly straightforward setup leads to unexpected and often counter-intuitive outcomes, highlighting the complexities of rational decision-making in strategic interactions.

We’ll explore the game’s mechanics, delve into the concept of backward induction, and examine how real-world scenarios can be modeled using the Centipede Game. We’ll also look at variations of the game and discuss the influence of factors like trust and reputation on player choices. Get ready to unravel the mysteries of this captivating game!

The Centipede Game is a fascinating example of game theory, highlighting the tension between cooperation and self-interest. It’s a bit like asking, if you were faced with a similar dilemma, would you act rationally, or would you make a more emotional choice? This makes me wonder about completely unrelated questions, like the one posed in this article: is thanos alive in squid game ?

Returning to the Centipede Game, understanding its dynamics helps us analyze strategic interactions in various real-world scenarios.

Game Mechanics of the Centipede Game

The Centipede Game is a fascinating game theory model that explores cooperation and strategic decision-making. It’s a sequential game with two or more players, each taking turns to either “cooperate” or “defect.” The game’s structure and payoffs are designed to create a tension between short-term gains and long-term outcomes.

Rules and Payoffs

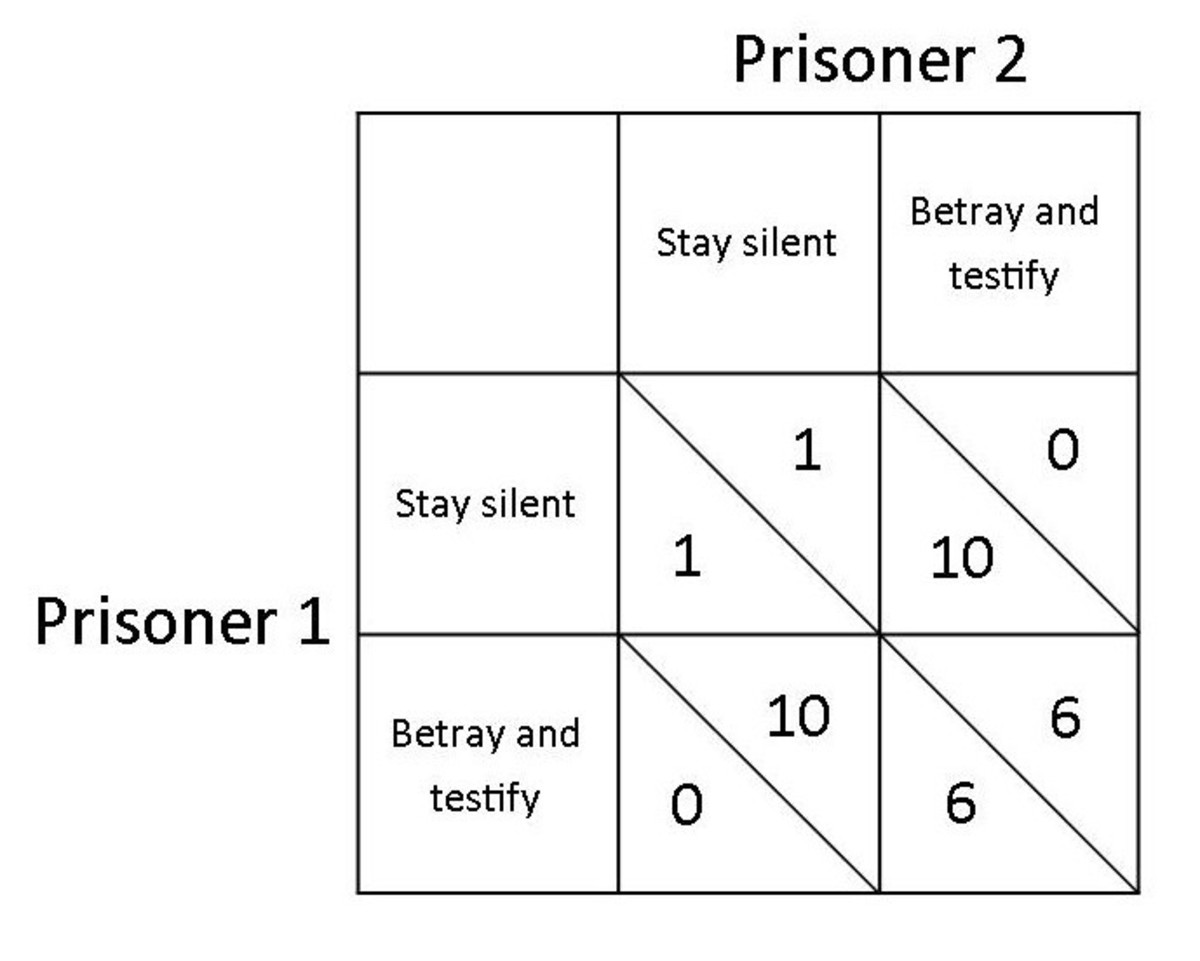

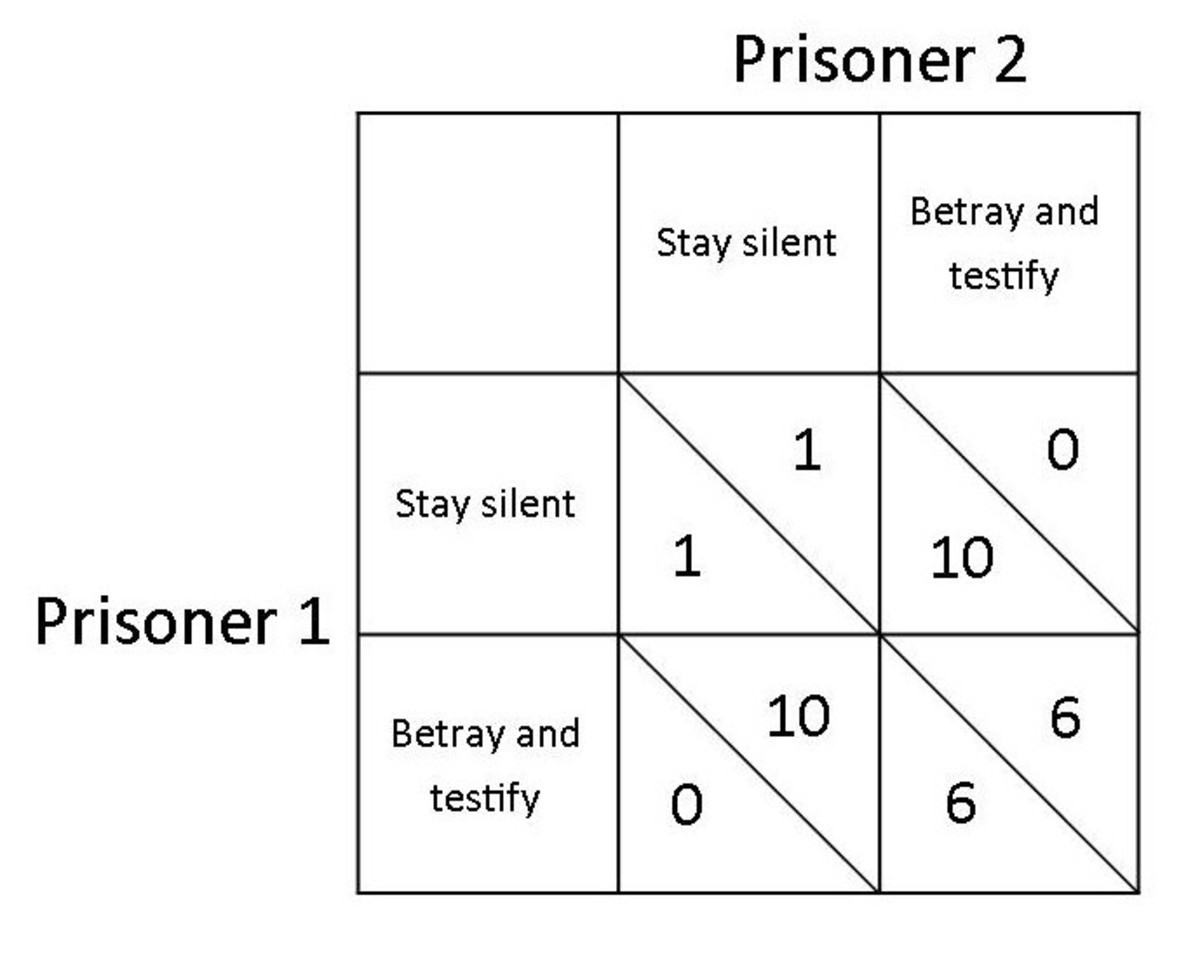

The Centipede Game begins with a small pot of money. Each player, in turn, can choose to either “cooperate” (pass the pot to the next player, increasing its value) or “defect” (take the pot for themselves). If a player cooperates, the pot’s value increases. If a player defects, the game ends, and the players receive their payoffs based on the pot’s value at that point.

Payoffs are typically structured so that defecting yields a slightly larger payoff than cooperating in the immediate round, but cooperating leads to larger overall payoffs if the game continues to its end.

Example Game Playthrough

Let’s consider a two-player game starting with a pot of $2. Player 1 can cooperate (pass the $2 pot to Player 2), increasing the pot to $4, or defect (take the $2). If Player 1 cooperates, Player 2 can then choose to cooperate (passing a $4 pot to Player 1, increasing it to $8) or defect (taking the $4).

If Player 2 cooperates, Player 1 gets to decide again, and so on. The game continues until a player defects or a predetermined number of rounds are completed.

Player Strategies

Players can employ several strategies:

- Cooperation: Always cooperating, hoping the other player will also cooperate, leading to the largest possible payoff.

- Defection: Always defecting, maximizing immediate gain regardless of the other player’s actions.

- Mixed Strategies: Employing a probabilistic approach, cooperating with a certain probability and defecting with another.

Game Tree Representation

The following table illustrates a simplified Centipede Game with two players and two rounds. Note that in reality, the game can extend for many more rounds.

| Player | Action | Pot Value | Payoffs (Player 1, Player 2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Player 1 | Cooperate | $4 | – |

| Player 2 | Cooperate | $8 | ($8, $0) |

| Player 1 | Defect | $4 | ($4, $0) |

| Player 2 | Defect | $2 | ($0, $2) |

Rationality and the Centipede Game

The Centipede Game highlights the tension between individual and collective rationality.

Backward Induction

Backward induction is a method of solving sequential games by working backward from the end of the game to determine the optimal strategy for each player. In the Centipede Game, backward induction predicts that the first player will defect immediately, as it’s the rational choice given the structure of the payoffs. Each player anticipates that the subsequent player will defect, making cooperation irrational at each stage.

Individual vs. Collective Rationality

The conflict arises because backward induction suggests that all players should defect, leading to a suboptimal outcome for everyone. Collectively, all players would be better off if they all cooperated. However, the fear of the other player defecting, and thus losing out on potential gains, leads to the rational choice being defection.

Observed Behavior vs. Prediction

Experiments show that players often deviate from the backward induction prediction. People frequently cooperate, even when it’s not strictly rational according to the model. This suggests that factors beyond pure rationality, such as trust, altruism, and the desire for reciprocity, influence decision-making.

Reasons for Deviation from Backward Induction

- Trust in the other player’s cooperation.

- Altruism and a desire for a fair outcome.

- Expectation of reciprocity (the other player will cooperate if they do).

- Aversion to risk.

- Bounded rationality – cognitive limitations in performing backward induction perfectly.

Variations and Extensions of the Centipede Game

The basic Centipede Game can be modified in several ways to explore different aspects of strategic interaction.

Game Variations, Centipede game

Several variations exist, including changes to the payoff structure, the number of players, and the introduction of incomplete information or uncertainty. Altering the payoff structure might incentivize cooperation more, while increasing the number of players complicates the decision-making process significantly.

Comparison of Variations

Variations affect the predicted outcome and strategic considerations. For example, a steeper increase in the pot with each round of cooperation might encourage more cooperation. Introducing incomplete information – where players are uncertain about the other players’ payoffs or preferences – adds another layer of complexity.

Remember the classic Centipede game? Its frantic, fast-paced action is a great example of early arcade design. For a different kind of cosmic challenge, check out the stunning visuals and gameplay in the comets video game , a more modern take on navigating a hazardous environment. Then, consider how Centipede’s simple but effective design compares to the complexity of modern game design exemplified by Comets.

Impact of Incomplete Information

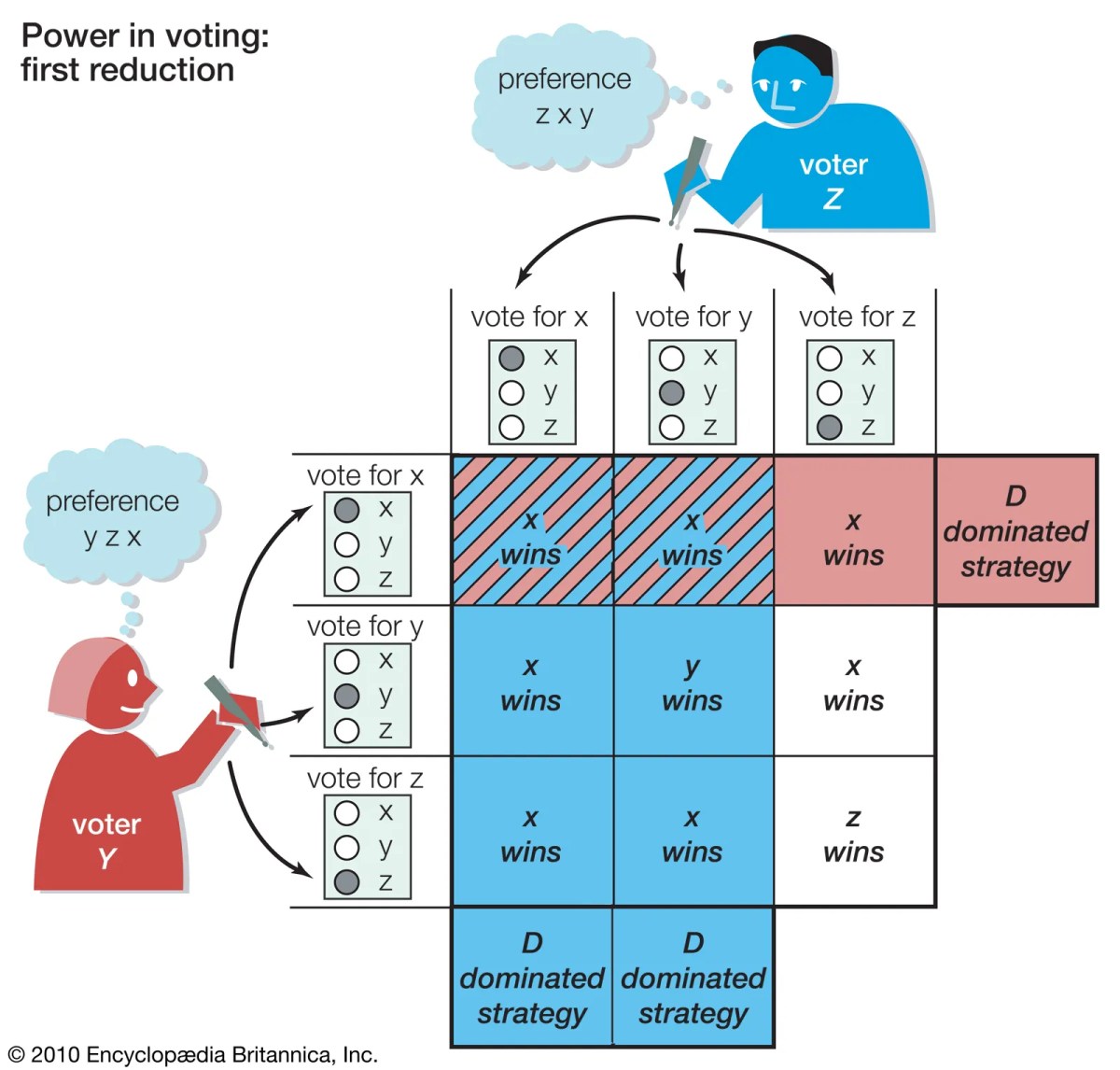

Incomplete information introduces uncertainty and makes it harder to predict the outcome. Players might use mixed strategies or adapt their behavior based on beliefs about the other players’ actions.

Summary of Variations

| Variation | Description | Predicted Outcome | Strategic Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increased Payoffs | Larger increments in the pot with each round of cooperation. | Increased cooperation likely. | Higher potential rewards incentivize cooperation, reducing the appeal of immediate defection. |

| More Players | Adding more players to the game. | More complex, harder to predict. | Increased risk of defection by at least one player, leading to lower overall payoffs. |

| Incomplete Information | Uncertainty about other players’ payoffs or preferences. | Highly unpredictable. | Players must form beliefs about other players’ actions and adapt their strategies accordingly. |

Real-World Applications and Analogies: Centipede Game

The Centipede Game’s simple structure provides a useful framework for understanding complex real-world scenarios.

Real-World Examples

Several real-world situations mirror the Centipede Game dynamic. Arms races between nations, where each side has an incentive to escalate, but mutually assured destruction is a disastrous outcome, are one example. Another example involves environmental conservation, where individual nations might exploit resources, leading to collective harm if none cooperate to protect the environment.

Detailed Analogies

In an arms race, cooperation would be disarmament or arms limitation treaties, while defection would be an arms buildup. In environmental conservation, cooperation might be agreements to reduce emissions, while defection would be continued pollution. The payoffs reflect the benefits of cooperation (e.g., increased security, environmental protection) versus the short-term gains of defection (e.g., military advantage, economic growth).

Implications for Human Behavior

The Centipede Game highlights the challenges of achieving cooperation even when it is mutually beneficial. It suggests that human behavior is influenced by factors beyond simple rationality, such as trust, social norms, and the anticipation of future interactions.

Hypothetical Scenario

Imagine two competing tech companies deciding whether to engage in a costly price war. Cooperating means maintaining current prices, while defecting means initiating a price war. If both cooperate, they maintain profits. If one defects, it gains market share and higher profits in the short term, but both companies suffer reduced profits if both defect in a prolonged price war.

Illustrative Examples

Three-Player Centipede Game

Imagine a three-player Centipede Game starting with a pot of $1. Player 1 can cooperate (passing $1 to Player 2, increasing it to $3), or defect (taking $1). If Player 1 cooperates, Player 2 chooses to cooperate (passing $3 to Player 3, increasing it to $9) or defect (taking $3). If Player 2 cooperates, Player 3 chooses to cooperate (passing $9 to Player 1, increasing it to $27) or defect (taking $9).

This pattern continues, with the pot tripling with each round of cooperation. Defection at any point ends the game, with payoffs distributed according to the pot’s value at that point.

Anti-Competitive Corporate Behavior

Consider two major corporations in the same industry. They face a choice: cooperate by adhering to fair competition practices or defect by engaging in anti-competitive behavior (e.g., price fixing, market manipulation). If both cooperate, they maintain healthy profits. If one defects, it gains short-term profits at the expense of the other. If both defect, they both face government fines and diminished consumer trust, resulting in reduced long-term profits.

Remember the classic Centipede game? Its frantic pace and challenging gameplay are iconic. Want a different kind of retro challenge? Check out this surprisingly addictive dress coat video game , it’s got a similar fast-paced feel but with a whole new aesthetic. After you’ve mastered that, maybe you’ll appreciate the simplicity of Centipede even more!

The corporation that defects first gains a short-term advantage, but if both defect, the outcome is worse for both than if they had both cooperated.

Trust and Reputation

In a repeated Centipede Game, trust and reputation become crucial factors. If players have a history of cooperation, they are more likely to continue cooperating, anticipating reciprocal behavior. Conversely, a history of defection can lead to a spiral of mistrust, resulting in defection by both players even when cooperation would be mutually beneficial. The potential for future interactions encourages cooperation.

Last Point

The Centipede Game, while seemingly simple, reveals profound insights into human behavior and the limitations of purely rational decision-making. The conflict between individual rationality and collective rationality is vividly illustrated, showing how even with the potential for mutual gain, self-interest can often prevail. Understanding the Centipede Game’s dynamics provides a valuable framework for analyzing various real-world scenarios, from economic interactions to international relations, where cooperation and trust are crucial for optimal outcomes.

Ultimately, it challenges us to consider the complexities of strategic thinking and the unpredictable nature of human choices.

Questions and Answers

What happens if a player chooses to “take” at any point in the Centipede Game?

The game immediately ends. The player who chose “take” receives a predetermined payoff, while the other player receives a smaller payoff (or nothing). The exact payoffs depend on the specific version of the game.

Is there a “winning” strategy in the Centipede Game?

According to backward induction (a method of solving game theory problems by working backwards from the end), the rational strategy is for the first player to “take” immediately. However, experimental evidence shows that people often deviate from this prediction, demonstrating the influence of factors like trust and risk aversion.

How does the number of players affect the Centipede Game?

Adding more players increases the complexity significantly. The potential for cooperation and the likelihood of defection become more nuanced, with more opportunities for betrayal and shifting alliances.

Can the Centipede Game be used to model real-world situations outside of economics?

Absolutely! It can be applied to various situations involving cooperation and trust, such as international negotiations, environmental agreements, or even personal relationships where decisions with short-term gains might lead to long-term losses for all involved.